By Dr. Doug Stilwell

In its more than 200 years of existence, public education’s purpose has been to ensure everyone has equal access to knowledge and skills, enabling participation in democracy, personal growth, economic success, and contributions to society. (Labree, 1997). Public education has certainly changed over time shifting its focus by responding to societal, political, and economic changes. In short, public education has evolved relative to the changing needs of society and with these changes, like many changes, controversy has resulted.

Throughout history, public education in the United States has faced significant challenges, including segregation, funding inequities, and ideological battles. Today, public education faces new challenges, which include the rise of movements like school choice, voucher programs, and privatization. Some critics often cite a lack of academic achievement as a reason for criticizing public education, pointing to standardized test scores or international comparisons, and it is these issues that are the focal point of this paper.

A Look at ACT Scores

Over the past thirty years, average ACT composite scores in the United States have experienced stability with typical variation, however with an obvious decline in recent years. This decline reflects systemic challenges in education, as the ACT objectively measures core academic readiness for college and careers. Unlike other metrics, ACT scores consistently show whether students are meeting academic standards, making it an important tool for assessing educational progress. In 1991, the average composite score was 20.6. This figure remained relatively stable through the 1990’s and early 2000’s, with expected year-to-year fluctuations. However, starting around 2016, a downward trend began. By 2023, the average composite score had decreased to 19.5, marking the lowest point in over 30 years.

An immediate response to this may be to point fingers and place blame on classroom teachers. Or accusations may be made about the overall quality of a school or school district. Each of these are not uncommon responses and speak to how we as humans look to find what seems to be an obvious reason when things don’t turn out the way we would like, as is the case for declining test scores.

However, this issue is much more complex than what some may think. While the concerns about achievement are valid, it can be argued that many factors, including socioeconomic discrepancies, drive these outcomes to some degree. Some may argue that even this may be an excuse, but I would argue it is not an excuse, but rather a significant contributing factor and our current reality.

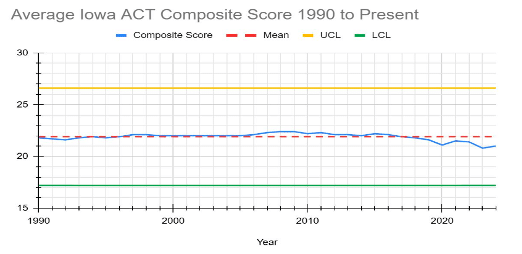

Even in my own state, ACT scores have remained fairly stable until the past several years. My former colleague and friend, superintendent Mark Lane recently shared the following ACT data with me:

As you can see from the figure above, although our state’s scores are higher than the national average, our downward trend follows that of the entire nation.

“So, who is to blame? Someone must be to blame.” This statement exemplifies a human tendency to assign fault when faced with challenges or failures. In the context of education, this can spark heated discussions about competence, responsibility, and accountability—hopefully revealing how flawed thinking has influenced past decisions and continues to shape present policies and actions.

In his book, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Dr. Peter Senge identifies 11 laws of systems thinking. Included in the 11 is the law that states, “There is no blame,” a sentiment which is often counterculture in the United States. “There is no blame” is a systems law that mirrors Dr. Deming’s belief that 95% of the results in a system are a result of the system itself, NOT THE PEOPLE.

Dr. Senge elaborates on this idea by sharing, “Systems thinking shows us that there is no outside; that you and the cause of your problems are part of a single system” (1990 p. 67). In other words, it’s the system that created the results.

Some may find this idea untenable for it seems that we’re saying no one is responsible. What I believe we are saying, however, is that no one IN the system is to blame. What I have come to believe through my studies and my own 44 years of experience is that those outside the system, those making laws and policies that govern education, bear the brunt of responsibility.

In other words, those who hold leverage on the system at large are responsible. Let me elaborate and provide evidence to support this point.

Recent Federal “Fixes”

In 2002 No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was enacted in the Bush administration. Its goal was for students to reach 100% mastery and to close achievement gaps. Its method included standardized testing and accountability. Schools failing to meet certain standards faced multiple penalties including school closure. Due to its draconian methods, it pressured schools to teach to the test, sometimes to the point of unethical practices (including cheating), which, as a result, narrowed the curriculum and learning opportunities for students.

NCLB violated several of Dr. Deming’s 14 Points. It increased dependency on inspection to achieve quality. It also failed to adopt any new philosophy and promoted a focus on numerical goals. Overall, as can be seen in the data, NCLB made no impact on ACT results, but certainly served to “drive in fear” and may have created a generation of students who now understood that successful test taking, rather than deep learning, was what was most important in their education.

Race to the Top (RTTT) emerged in 2009 under the Obama administration as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). It was intended to promote innovation in order to transform education. While it also focused on teacher quality, it still relied heavily on accountability as a major tenet. RTTT was a competitive grant program that pressured schools to conform and amplified inequities, as wealthier states had more resources to develop stronger applications than states with lower socio-economic status.

This exacerbated achievement gaps and left some states further behind. Rather than eliminating them, RTTT strengthened barriers between states, given the competitive nature of the program. It drove in fear, as teacher evaluations, and in some cases compensation, were based on test results. It also focused on numerical goals. Similar to NCLB, we see no impact on ACT scores as a result of RTTT.

Rounding out three significant federal programs is the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). ESSA was designed in 2015 during the Obama administration to provide states greater flexibility relative to education policy while maintaining federal oversight and shifting the emphasis from punitive accountability to more supportive interventions.

Unfortunately, ESSA still required a dependence on inspection (testing) to substantiate the achievement of its goals. While there was greater flexibility than its predecessors, barriers still existed between schools and school districts, as it did not explicitly encourage collaboration. In the end, while ESSA empowered states and supported greater flexibility, the outcome was the same: no improvements in ACT results.

In Iowa

Even efforts in my state have been fruitless. During this same time frame the “core” standards were adopted and teacher and leader standards were revised. Year after year, annual evaluations have been conducted, accompanied by ongoing training on how to improve the evaluation process—what Dr. Ackoff would call learning to do “the wrong things righter.” Legislatively, over this 30-year time period we’ve seen upwards of 70 education-focused bills that were passed.

And, in the end, we saw no improvement in our state’s ACT scores, but rather the beginning of a decline the past several years.

We Need Profound Knowledge

There is a strong argument to be made that the more directive and controlling federal and state governments have been, and the more local educators have been left out of the decision-making process, the poorer the educational results we see (Lane, personal communication, 2024).

What is needed by leaders at all levels, including state and federal government, is what Dr. Deming referred to as “profound knowledge’” about education. This includes a deep understanding of the system’s structure, its overarching aim, and how its various parts interact and work together. It requires acknowledging that variation in needs and outcomes is inherent in any system, along with understanding how change affects people, what drives their motivation, and how to foster meaningful engagement.

A critical part of gaining this profound knowledge is the absolute need for leaders to honestly seek meaningful feedback from, and actively listen to, those working within the system before making any adjustments. By valuing the insights of educators and others directly involved, including students, leaders can ensure that their decisions are informed by practical realities and aligned with the needs of the system. Lastly, leaders must develop a practical understanding of improvement science to drive effective and sustainable progress.

Dr. Deming was adamant that leadership that excluded the input of the people actually performing the work led to poor decisions, inefficiencies, a lack of understanding by leadership about the realities of day-to-day operations, and poorer results. This is exactly what has happened in education. Dr. Deming was highly critical of this approach and advocated for leaders to listen to the voice of the worker and treat them as essential contributors to the organization’s success.

In an amusing scene from the 1985 film Back to the Future, Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) travels back in time to the 1950s and meets a younger version of his friend and inventor Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd), that offers an apt and amusing anecdote about the misguided concept of progress and improvement. During their first encounter, Doc uses a strange contraption to try to read Marty’s mind, but the device fails miserably. Marty then explains that he traveled from the future in a time machine that Doc himself had invented. Pausing with the perfect mix of shock, disbelief, and insight on his face, Doc grabs Marty by the shoulders and exclaims, “My god, do you know what this means? It means this damn thing doesn’t work at all!”

For me, this quote rings true about legislative efforts to improve education. Without fully understanding the complexity of the education system and how its many moving parts interact, these top-down efforts simply don’t work. In other words, according to journalist satirist H.L. Mencken, “For every complex problem, there is a solution that is clear, simple, and wrong” (1920, emphasis added).

A Better Approach

Education and government would both greatly benefit from embracing and applying systems concepts and practices advocated by thinkers and authors in systems leadership like Dr. W. Edwards Deming, Dr. Russell Ackoff, Dr. Margaret Wheatley, Dr. Peter Senge, and Dr. Donella Meadows. By deeply understanding and integrating these principles, we can move past unsuccessful short-term fixes and fragmented approaches to achieve sustainable, transformative results that align with our shared goals for progress and equity.

Without this shift, efforts to improve performance are likely to fail, just as Dr. Russell Ackoff warned: “Until managers take into account the systemic nature of their organizations, most of their efforts to improve their performance are doomed to failure.”

Ackoff’s observation highlights the critical need for those working on education systems to understand their systemic nature. Yet, far too often, efforts to reform education get stuck in a loop of reworking familiar ideas and strategies instead of looking for innovative approaches. This brings me to one final point about our educational system: the importance of broadening the perspectives of those shaping it.

In what seems to be an all-to-frequent practice, leaders and policymakers confine themselves to the same strategies or recycled concepts that they might have experienced in their own educations, failing to address the true complexity of the current system. In addition to listening intently to those in the system, real change requires, in my opinion, looking beyond the field of education for fresh perspectives and innovative ideas. Without such, the same patterns of thinking that created the problems in the first place will continually recycle – like going nowhere fast.

I’m reminded of a line from the movie Good Will Hunting. In a conversation between the characters played by Matt Damon and Robin Williams, Damon’s character, a brilliant but troubled self-taught mathematician working as a janitor at MIT, critiques the books on Williams’ character’s bookshelf, saying, “You people baffle me. You spend all your money on these fancy books; you surround yourselves with them… and they’re the wrong books” (expletive omitted, 1997).

While this may be an overstatement, it gives us pause to think about how often those working in and on education systems rely on the same approaches (“wrong books”) and fail to seek new insights. In doing so, they’re “washing dishes in dirty water”—trying to make improvements without ever questioning or replacing the very ideas they’ve been using.

A good place for leaders to begin is by “adopting a new philosophy.” As Albert Einstein famously observed, “We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them.” Without a transformational shift in thinking, decisions will be made at the same level of thinking where the problems were created.

Adopting a new philosophy, however, requires an open mind and a willingness to explore new ways of understanding and addressing challenges. Leaders can develop a greater understanding by developing the aforementioned “profound knowledge”—and by listening carefully and frequently to those working within the education system to understand its realities.

These fresh perspectives can provide the knowledge and tools to help leaders design and refine systems that better support educators and students. Until leaders adopt a new philosophy and commit to these changes, we will likely continue to see the same outcomes from state and federal legislation: significant, but misguided, effort with little meaningful progress.

References

Ackoff, R. L. (2006, October 8). Doing the wrong things righter. Curious Cat Management Improvement Blog. Retrieved from https://management.curiouscatblog.net/2006/10/08/doing-the-wrong-things-righter/

Ackoff, R. L. (2010, March 17). If Russell Ackoff had given a TED talk [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OqEeIG8aPPk

Labaree, D. F. (1997). Public goods, private goods: The American struggle over educational goals. American Educational Research Journal, 34(1), 39–81.

Mencken, H. L. (1920). The divine afflatus. In Prejudices: Second series. Alfred A. Knopf.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday/Currency.

Van Sant, G. (Director), & Weinstein, H., Weinstein, B., Damon, M., Affleck, B., & Skarsgård, L. (Producers). (1997). Good Will Hunting [Film]. Miramax Films.

Zemeckis, R. (Director), & Gale, B. (Writer). (1985). Back to the future [Film]. Universal Pictures.

They are failing because enough time has passed that former failures are now teachers

Those teachers don’t know science or civics to pick two egregious examples.

I’ve taught for 10 years at the college level

To your comments, which I agree with, I would add that it’s a shame Dr. Deming’s principles are not required in our colleges and universities.