Guest Post by Dr. Doug Stilwell, Drake University

Little drops of water,

Little grains of sand,

Make the mighty ocean

And the pleasant land.

Verse One of the 19th Century Poem “Little Things” by Julia Fletcher Carney

More than one book or article has been written on the subject of change. Although this does not represent the actual number of singular materials, when I Googled “Organizational Change,” the search page indicated there were about 148,000,000 results located in just a half a second. Attempting to learn about and implement change can feel as challenging, and sometimes nebulous, as trying to learn leadership, for as Warren Bennis wrote in 1959, “ . . . probably more has been written and less known about leadership than about any other topic in the behavioral sciences” (p. 259). The same might be said of change.

But, why do we find change to be so difficult when Heraclitus, the ancient Greek philosopher, once said that “Change is the only constant?” Change, in general terms, is a very natural process, for it is simply the act of making something different. But the change being discussed here is more than simply making something different; it is the act of making something better (aka making improvements) through the change process.

One could spend hours surfing through the 198,000,000 “hits” on the internet related to the question, “Why is organizational change so difficult?” Rather than pursuing that method, the purpose of this writing is to simply explore one simple and plausible reason organizational change/improvement can be difficult and unsuccessful.

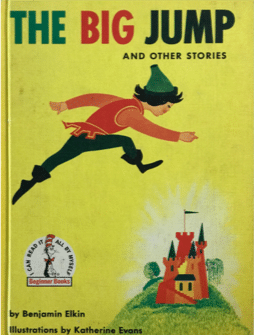

When I was a kid and learning to read, my parents purchased a set of books known as the “I Can Read it All by Myself Beginner Books,” founded by Phyllis Cerf, Ted Geisel (aka Dr. Suess), and his wife Helen Palmer Geisel, designed for beginning readers. Lately as I have been contemplating the challenges to changing/improving/transforming education, one of those beginner books came to mind: The Big Jump, by Benjamin Elkin.

The Big Jump is a story about a little boy, Ben, who lives in a kingdom where only the king may own a dog. One of the king’s dogs takes a liking to Ben and, despite his desire to do so, Ben cannot own the dog for he is not a king. The king shares that Ben can become a king, but he must complete a task known as the “big jump.” The “big jump” consisted of jumping from the ground to the top of the king’s castle, which the king demonstrates in one giant leap. With new-found hope for owning a dog, Ben goes home and begins to practice; jumping successfully to the top of one box, then two – but then failing to jump to the top of the third box. Ben then finds a long stick and learns to vault himself to the top of four boxes, but no higher, leaving Ben feeling frustrated. The boxes Ben has attempted to scale now sit stacked in a stair-like fashion when the dog, whom the king allowed Ben to have overnight, jumps from the first box to the next and the next until he reaches the top box, igniting a paradigm shift for Ben relative to the challenge he faces. The next day, Ben returns to the king’s castle to take on the king’s “big jump” challenge. Since the king did not dictate a specific method for attacking the challenge, having learned from the dog’s approach from the day before, Ben begins to jump from step to step up the castle stairs until he successfully reaches the top. In the end, having literally approached the task one step at a time, Ben earns the right to become the owner of the little dog who taught him to jump to the top of the castle.

I have been a part of and have heard many stories about unsuccessful attempts at change in education. Based on the lesson from The Big Jump story, I have come to the conclusion that one reason change might be difficult is, despite our best intentions, the changes we seek to undertake can be extremely large and complex. Part of this dilemma may be “hard-wired” into us as educators, something I discovered during my years as a school and district leader when I often asked teachers what drew them into the teaching profession. While there was some variation of responses, a major theme that emerged was that educators want to change the world and make it a better place; something which continues to ring true for me as well to this very day. However, herein lies the challenge: the “world” is a pretty big and convoluted place and changing/improving it would be an enormous and complex task. The old adages of “Biting off more than one can chew” and “Your eyes are bigger than your stomach” are apt metaphors for this desire to change the world. Even changing the world of education itself is daunting, and the same can be said for trying to change/improve a district, school, or even a classroom…unless we have the right mindset, knowledge and skills.

Children’s stories can have wonderful lessons for adults. In this case, The Big Jump can remind leaders of the importance to frame and facilitate change in manageable bites that can lead to improvement without being overwhelming. In the story, Ben learned that he did not have to cover the distance from the ground to the top of the castle in one fell swoop. Rather, he learned that he could take it step by step until he reached his goal. The same is true for making educational changes/improvements. Change, in this way, is similar to effective long-term teaching and learning. An effective and wise teacher would certainly not expect students to know and understand the content of a year-long course in just one day, week, or even a month, for that would likely make even the most confident of students wither and lose hope. What effective teachers do, is break down the course objectives into smaller, interrelated parts and build the appropriate instructional “scaffolding,” providing support and allowing students to learn at a pace that is appropriate for them, facilitating long-term retention and knowledge building. Concept-by-concept and skill-by-skill, students’ progress “up the ladder” of learning until they successfully grasp, or master, the overall objectives for the course.

I have often said that a successful leader is also an effective teacher. Dr. Peter Senge, in his book The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of a Learning Organization, supports this idea when he identifies “leader as teacher” as one component of the “new work” of leaders. When leading change, if leaders will think and work like exceptional teachers who expertly design effective learning systems for their students, they will see the need to break down daunting “difficult to swallow” goals into manageable, interdependent tasks that can be accomplished over time. Too large of a goal without a reasonable/manageable timeframe and the necessary “scaffolding,” will likely result in people feeling, rightfully so, overwhelmed and defeated. Wise and effective leaders will, with the input and support of those they lead, develop a plan for change/improvement that can be more easily accepted, consumed, and achieved.

My Grandmother Stilwell, a former teacher, owned a book entitled The Family Book of Best Loved Poems that I would often read through when I spent the night. One of my favorite poems – one of first poems I ever recall memorizing – was entitled “Little Things,” written by Julia A. Fletcher Carney. It, too, speaks of how the monumental often originates with the humblest of beginnings:

Little Things

Little drops of water,

Little grains of sand,

Make the mighty ocean

And the pleasant land.

Thus the little minutes,

Humble through they be,

Make the mighty ages

Of Eternity

The wisdom of this poem and the insights from The Big Jump might be helpful to leaders at all levels of education if we are to make meaningful change/improvement. As educators, we should be driven by great visions and goals, but we need to be able to make the process to achieve them manageable and transparent so that those we lead can see the path without being overwhelmed and achieve each of the interdependent steps necessary to “get there.”

There are indeed many reasons change efforts fail. But we can avoid one of those reasons by taking “small jumps;” breaking down important change/improvement efforts into manageable and measurable steps so that the daunting size and complexity of initiatives are not the cause of failure.

References

Bennis, W G (1959). “Leadership Theory and Administrative Behaviour: The Problems of Authority,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 4, 259-301.

Carney, J. (n.d.). Little things. In D. George, The family book of best loved poems (p. 194). Hanover House.

Elkin, B. (1958). The big jump. Random House.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Currency.

The article had some great insight into the world of change (improvements). I enjoyed the story of “The Big Jump”. This story showed that tasks can be broken down into little steps rather than attempting to take the whole task head on. This also allows me to think of the PDSA cycle. The cycle lets you plan one way and then do the task, reflect and adjust your original plan if needed.

We have spent so much of our graduate course work on the idea of what makes an effective leader or teacher. Effective teaching and leading boils down to having the strategies, knowledge, and systems in place to impact student outcomes. They are willing to make improvements (change efforts) OVER TIME for the betterment of learning and achievement.

This article also made me think about our usage of the words improvement and change and how they are not completely synonymous. Improvement implies movement or action from one state to another while change indicates making something different. We have to remind ourselves how many change efforts fail and by using the PDSA process, we can spend more time finding effective ways for improvement that allow us to study, make a “big jump”, and back to the drawing board if needed.

This line in your post, “When leading change, if leaders will think and work like exceptional teachers who expertly design effective learning systems for their students, they will see the need to break down daunting “difficult to swallow” goals into manageable, interdependent tasks that can be accomplished over time,” solidified the importance of the Plan, Do, Study, Act improvement cycle. With this improvement cycle, building goals, or ITDTPs don’t seem such a daunting, disconnected task for a teacher and/or leaders. A PDSA allows tasks to be managed in a way that can be adjusted and celebrated for growth, in real time; not at the end of the year. As leaders its important for us to be rid of ‘Fixes that Fail,’ and lead in a way towards sustainable growth.

This post had some great insight into this idea of how to implement change. I completely agree that sometimes the changes we want to make are complex or extremely large where we may not have the leverage to implement the change. Using the “The Big Jump” and the poem “Little Things” has helped give a deeper understanding to this idea of change. Throughout the classes at Drake University, we have the opportunity to learn with Dr. Stilwell about the way to implement systematic change. One piece that struck me through reading this was the tool time book in which we use a variety of tools to implement the Plan, Do, Study, Act cycles for continual improvement. These tools help us complete the change one step at a time, just like the little boy Ben from “The Big Jump.” Attributing this story and poem helped me see how important it is to use an improvement cycle tool such as PDSA and the tools from the tool time book. This will ensure that as we start to implement change that the change is not to large or complex to where we don’t have leverage. Change one step at a time can be more beneficial so that it creates improvement, not just change for the sake of change.

As I was reading this article, I was reflecting on the Plan, Do, Study, Act cycles that I have engaged in during my graduate coursework so far. When I think of the Plan, Do, Study, Act cycles (furthermore known as PDSA cycles), the small changes implemented from the PDSA cycles have made the biggest impact. As I have dove into the PDSA cycles, when focused on a problem within our current system, the first answer isn’t to scrap the whole system and start new, but rather to make small subtle changes to receive desired results. However, when thinking about systematic change, districts change curriculums or processes entirely instead of making small changes to obtain desired results, which is a huge undertaking and sometimes ends up becoming more problematic in the long run. Those changes then are not often sustainable.

I enjoyed reading this article and being able to connect it to the learning in my graduate course work. When thinking about quality improvement in education, there is much to consider. I have learned that slow, gradual progress that works to solve a given problem without negatively effecting other parts of the organization takes a strong, servant leader, a true team of teachers/staff members, and small steps that are implemented, supported, and reflected upon before proceeding. In my experience, I have found that so often in education we attempt to solve a large problem in a large way, implement something entirely new into an organization to fix a relatively small problem, or we turn to “best efforts” instead of using knowledge to genuinely improve. I enjoyed the ideas from this article about taking small steps, and thinking about the problem in a new way. Going about problem solving in a manageable way that can be maintained and monitored is a crucial part of making that quality improvement to an organization.