Guest post by Mark Graban

As I wrote about in my first post, my first job out of college was at the GM Livonia Engine Plant, outside of Detroit. General Motors wasn’t my ideal workplace after having read Deming’s Out of the Crisis and learning a bit about Lean manufacturing in college. If possible, I wanted to work in something closer to the Deming environment. But, I needed a job, so I cast a wide net.

To my surprise, during the interviewing process, GM promised me a different type of workplace (one that existed, at least, at this plant), one based on the Deming philosophy. I was probably the only kid coming out of college who recognized or cared about that. But, it really mattered to me.

Sadly, it didn’t take very long to realize that the plant had a very traditional management style, very traditionally combative labor/management relations, and a typical blame-and-shame, command-and-control environment that made people miserable and didn’t deliver quality to the customer or any of the right business results.

What had happened? I was told that Dr. Deming had taught some workshops within GM, particularly the Powertrain division in the 1980s. A forward-thinking plant manager modified the Deming Philosophy to create something called “The Livonia Philosophy.”

But, after a period of success, that plant manager was promoted and the new plant manager, essentially hit the “undo” button on all of the Deming stuff. There were still posters in the hallway glass cases celebrating the new approach. But, it was no longer the daily reality in the plant. I’ve blogged about some of the problems and chaos on my blog before.

One of my colleagues gave me a copy of a “Livonia Philosophy” handbook that was gathering dust, and I’ve kept it to this day.

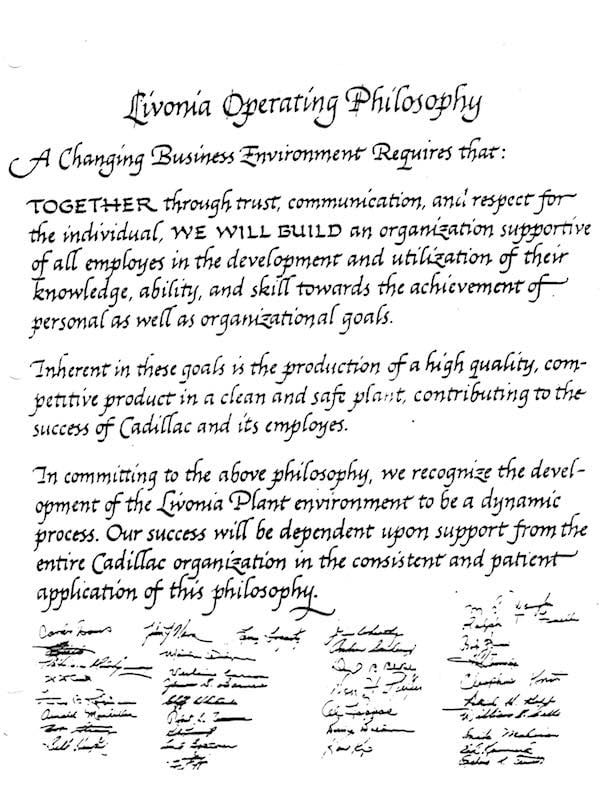

The first page says “The Livonia Operating Philosophy” is born from “a changing business environment requires that together through trust, communication, and respect for the individual, we will build an organization supportive of all employees in the development and utilization of their knowledge, ability, and skill towards the achievement of personal as well as organizational goals.”

Wow. That sounds very much like the Toyota Production System and Lean management. Toyota talks about “respect for people” or “respect for humanity” as an “equally important pillar” of their Toyota Way management philosophy (the other being “continuous improvement”). The Livonia plant didn’t have a lot of trust and mutual respect. Without that, the communication mainly came in the form of yelling and screaming when results were poor.

Speaking of continuous improvement, my GM plant also had a very traditional “suggestion system,” not a Kaizen-style approach to improvement. It certainly wasn’t a “culture of continuous improvement” and there wasn’t any “quality culture” to speak of. People weren’t working together toward personal and organizational goals… and that environment was, I’d say, management’s fault.

The Livonia Philosophy (as written, not practiced) also sounds like Lean in the goal of utilizing all people’s skill and creativity, as we practice in the Kaizen model. Toyota sometimes talks about the primary goal of improvement efforts to be learning and the development of people, with improved metrics being a secondary goal. What a progressive view that was back in the 80s. It’s a shame it was long gone by 1995 (thanks for misleading me in the interviews, GM).

The document continues by saying, “Inherent in these goals is the production of a high quality, competitive product in a clean and safe plant, contributing to the success of Cadillac and its employees.”

We didn’t have high quality – the data and many quality “spills” proved that. The plant wasn’t clean – the floors were slippery with oil and grease (I slipped and fell once) and I still wonder if I harmed my health by breathing air that was full of coolant mist, something the union complained about constantly. Safety wasn’t the primary focus – making the production numbers was more important, as I saw demonstrated in many ways.

The document continues, “In committing to the above philosophy, we recognize the development of the Livonia Plant environment to be a dynamic process. Our success will be dependent upon support from the entire Cadillac organization in the consistent and patient application of this philosophy.”

Instead of development, we got regression, apparently.

If this philosophy was really the right approach for the business, how could it slip away? How could GM install a new plant manager who was, apparently, so willing to undo that progress?

The same thing happens today in some healthcare organizations. As I blogged about previously, there was one hospital system that had been written up as a Lean success story in a major healthcare publication. Less than a year later, a new CEO came in from the outside and disbanded the internal Lean program. A similar thing happened with one of the hospitals I featured in the first edition of my book Lean Hospitals, when a new CEO came in and made it clear that Lean was no longer needed.

I guess it goes to show how difficult it is to change an organization’s culture and how fragile that new culture can be. Have you lived through similar situations before? What can we do to prevent similar situations in the future?

Mark Graban is author of the book Lean Hospitals: Improving Quality, Patient Safety, and Employee Engagement (Productivity Press), which was selected for a 2009 Shingo Research and Professional Publication Award (3rd Edition, 2016).

Mark also co-authored Healthcare Kaizen: Engaging Front-Line Staff in Sustainable Continuous Improvements, which was released in June 2012 and also a Shingo Research Award recipient in 2013.

He is the founder and lead blogger and podcaster at LeanBlog.org, started in January 2005.

Mark is also the Vice President of Improvement & Innovation Services for the software company KaiNexus.

Hi Mark,

I just came across this interesting comment from an engineer at a GM plant:

“I worked at a small GM Division and we hired Dr. Deming to coach us on his methods. I think it must have been very close to the same time that he was working with the Fiero team. Prior to that, we had experienced a period of very high demand that led to a quantity vs. quality attitude but eventually high costs due to low quality threatened the business.

Dr. Deming’s coaching was exactly as xxx described….statistical quality control, but there was also a very heavy layer of empowering employees to make decisions in the best interest of the process which the video highlights. We had drawings with all dimensions and tolerances required for every part of an assembly. Dr. Deming gave us a lot of grief ( why do you allow any variation?) and we eventually got rid of the tolerances. The tolerances permitted were based on the measuring tool’s capability ( and oh by the way do you have control over the process of calibrating your measurement tools).

I think management did not realize what they had signed up for and all levels of employees were challenging how we did things and whether it met the Deming Principles. Eventually, the Deming method became ingrained and our quality was better than any other division within GM. We realized that higher quality=lower cost which was 180 degrees from conventional thinking. Thanks in part to Dr. Deming I had a very rewarding career.

“