Guest Post by Dr. Doug Stilwell, Drake University

Julie sat in the last row on the right-hand side of the classroom near the window, two or three seats from the front. Having just finished what I thought was a pretty good math lesson, I asked the class if there were any questions. Julie’s hand immediately went up in the air. “Yes, Julie, what can I help you with?”

“Mr. Stilwell,” she responded, “when am I going to ever use this?”

This was not the technical sort of question I was anticipating and taking a fleeting moment without reflecting on the depth of what she was asking me, I glibly responded, “Julie, you will use this when your ‘real life’ begins.” I recall feeling pretty good about my response, smugly thinking it was an adequate answer for a 12 year old. I retreated to my desk, turned to sit back down and saw Julie’s hand vigorously raised one more time.

“Yes, Julie?” I asked with some frustration in my voice.

“But Mr. Stilwell, this is my real life, right now.”

Pause… “I guess it is,” I replied. End of conversation.

I share this story with students in the courses I teach and I jokingly tell them, as I finish the story, that I learned one valuable lesson that day….not to call on Julie anymore! However, all kidding aside, there was a powerful lesson here to be learned; one that may have transformed me as a teacher… and I missed it. Rather than seizing this as an opportunity to develop a new theory on which I might improve student engagement and learning, I focused not on what was on the minds of my students but on improving my pedagogy; reinforcing, perhaps, how to continue to do the wrong things – things that had no relevance for my students – better.

Dr. Russell Ackoff is renowned for the adage, “Stop doing the wrong things ‘righter’” and this motto has perfect application to my interaction with Julie that day, approximately 30 years ago. Technically, my lesson was sound. Unfortunately, it did little to connect with and have meaning for students, for I assume Julie was the only one brave enough to ask such a challenging question, while others, likely focused on “teacher pleasing,” may have been wondering the same thing. It is a lesson that highlights the wisdom needed to determine what the “right” things are in our work as leaders.

In one of his conversations found on YouTube and posted on January 11, 2010 (the year following his death), Dr. Ackoff provides the following insight about leaders doing the “right and wrong” things in the systems they lead:

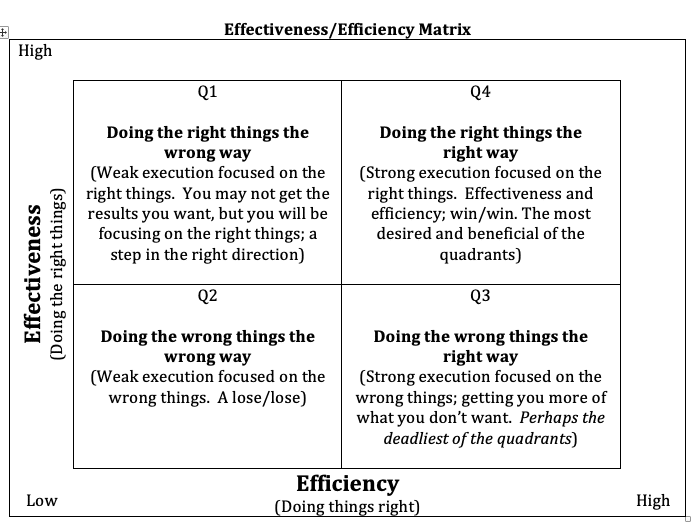

Peter Drucker said, “There’s a difference between doing things right and doing the right thing.” Doing the right thing is wisdom, and effectiveness. Doing things right is efficiency. The curious thing is the righter you do the wrong thing the wronger you become. If you’re doing the wrong thing and you make a mistake and correct it you become wronger. So, it’s better to do the right thing wrong than the wrong thing right. Almost every major social problem that confronts us today is a consequence of trying to do the wrong things righter” (Haynes, 2010).

The following matrix may make simpler sense of this concept. Note particularly the significant and profound difference between quadrants three and four.

Effectiveness/Efficiency Matrix

Learning to do things “right” is important and all sorts of training exist for doing so, including Lean Six Sigma, Kaizen, Plan-Do-Study-Act, Statistical Process Control, and ISO certifications, to name just a few. I do not believe Dr. Ackoff was downplaying the need for efficiency, but rather was saying that it may be counterproductive to do things right if we were not doing the “right” things. In fact, he makes the case that we will likely make things worse (or, “wronger”) by doing the “wrongs things ‘righter,’” yet another method to sub-optimize a system. This was certainly the case in my own example above.

Doing the “right things” may well tie into what Daniel Pink describes as the “purpose motive,” one of the three key attributes (autonomy, mastery, purpose) necessary to ignite intrinsic motivation. Simon Sinek refers to this as well when he describes his “golden circle” concept, telling us that working and leading from “why” (the reason an organization exists) is deeply rooted in our biology, as it connects deep within people’s brains – their limbic systems – the seat of basic human emotion. Stephen Covey similarly described this concept using the metaphor of a ladder, stating, ”Management is efficiency in climbing the ladder of success; leadership determines whether the ladder is leaning against the right wall” (Covey, 2011).

It is likely that few would argue the importance of focusing efforts on the “right things.” However, while it may be a fairly straight-forward task to teach a management or improvement process to someone, the real challenge may lie in first determining what is “right” to do in any given context.

Dr. Ackoff indicated that wisdom is necessary in determining the right things to do. However, while some individuals may be imbued with wisdom inherently or through their own life’s experiences, paving the way for making wise personal decisions, this may not hold as true when leading a complex organization. To that end, Dr. Deming might well ask, “By what method” can we determine the “right” things to do? Wisdom, from this perspective, may be in discerning the need for a process, without which we may be forced to rely entirely on one’s intuition.

I want to share one process used by a friend and former colleague during this, his first year as school superintendent, to determine “what’s right” for the students, district, and community.

Mark Lane is the superintendent of the Decorah Community School District in Decorah, Iowa. Mark possesses a great deal of profound knowledge, having dug deeply into Dr. Deming’s work over the past ten years. That profound knowledge combined with a command of the Baldrige Excellence framework has helped Mark to lead and facilitate the district’s work to determine “the right things” for the Decorah schools.

To answer the question, “By what method,” Mark has responded with the following powerful statement:

Listen to the hopes, dreams, and aspirations of the people closest to the work, and then make that desired state seem possible.

(Mark Lane, 2019)

Based on that mindset to drive the work, upon his entry into the district Mark used the bone diagram process in his Baldrige-based entry plan to “listen” to those people closest to and most directly impacted by the district’s work in order to get a sense of the district’s current state. In doing sohe found there were well-meaning, hard-working people working without a clear aim and implementing random acts of improvement, resulting in frustration, blame, animosity and resistance among professionals. He then used the bone diagram process to again listen to stakeholders to determine their desired state for the district. The desired state included well-intentioned hard-working people functioning interdependently with clarity and coherence to optimize and achieve the aim of the system and to develop a sense of pride and joy in work, innovation, and collective efficacy.

The next step in the process was to engage a representative group of district stakeholders, the School Improvement Advisory Committee (SIAC) in answering the following questions over the course of two meetings:

- Meeting One:

- How might a public school monitor excellence in educational and operational service?

- Meeting Two

- What are we trying to achieve in key focus areas?

- What promises are we making to our key stakeholders?

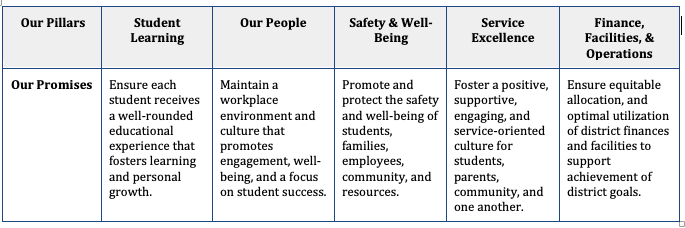

Using quality tools including the affinity diagram and P3T (paper, passing, process tool) processes, the SIAC committee developed the following strategic pillars and promises:

Next, the pillars and promises (customer requirements) were shared with staff who then responded to a mission-vision-values (M-V-V) survey. Once the survey feedback had been gathered and analyzed (Mark is a doctoral student at Drake University and utilized qualitative research methodologies including in vivo coding, theoretical coding, and member checking), the new mission, vision, and values were crafted and ultimately approved by the school board. In other words, through this process and under Mark’s leadership, the Decorah Community School District uncovered what the “right things” were and encoded them into its:

Shared Mission:

Learning – Thriving – Creating our Legacy

Vision:

Decorah Community School District will be a collaborative, innovative, learning-centered organization empowering students to embrace their personal strengths and create their future.

Values:

Collaboration and community; curiosity and creativity; engagement and excellence; equity and well-being; integrity and humility; stewardship and sustainability

Following an examination of the pillars, promises, and M-V-V, there is little question in my mind regarding what the Decorah Community School District values and what they have determined to be “right” for them. Wisely, Mark did not come into the district with his own ideas regarding what was most important for the district, but rather relied on his background with Dr. Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge, his knowledge of the Baldrige Performance Excellence Framework, and his experience with process improvement to engage the district and community in a well-planned process to uncover what was most important for those he is charged with leading. Is Mark Lane’s approach the only way? No, for as the saying goes, “There is more than one way to skin a cat.” However, the principles that guided the district’s work are universal and the manner in which they were operationalized in Decorah have proven to be a very effective technique that certainly address Dr. Deming’s question, “By what method…?”

How much better and more meaningful might my sixth grade students’ learning experiences have been had I possessed “profound knowledge” and provided a better response and method to process Julie’s heart-felt math question of “When am I ever going to use this?” My woeful response those 30 years ago haunt and compel me to carry forth with this profound work, “preaching to the masses and working with the willing” to transform learning and education. Working to discern the “right” things is the role of leadership and, as we have seen from Mark Lane’s example, there are effective methods that can be employed to unlock what is in the hearts of people who have a stake in a school, school district, or organization of any type.

Let’s learn to do the “right things ‘righter’.”

Want More?

For the latest updates, events, and learning opportunities, subscribe to our mailing list today!

References

Covey, S. (2011). “Leadership and Management.” Retrieved from https://leadershipforlife.wordpress.com/2011/08/23/hi/

Haynes, P. (2010, January). Russell Ackoff / Studio 1 Network [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MzS5V5-0VsA&feature=emb_logo.

Pink, D. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. New York: Riverside Books.

Richardson, W. (2016, March 17). “We’re Trying to do the ‘Wrong Things Right’ in School.” Modern Learning. Retrieved from https://medium.com/modern-learning/we-re-trying-to-do-the-wrong-thing-right-in-schools-210ce8f85d35#.6293musst

Richardson, W. (2015, November). “The Surprising Truth about Learning in Schools” [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxyKNMrhEvY&feature=youtu.be.

Sinek, S. (2009) Start with why: How great leaders inspire others to take action. New York: Penguin Group.

I appreciated hearing about the initial approach Mr. Lane took in his new school district. He used quality tools (bone diagram, affinity diagram, P3T, etc.) to get input from various groups and specifically the people closest to the work. It is important to get things written on paper, as they did with their pillars and promises, so that all of the arrows could align. The interdependent nature of the system could then thrive. I would say things are “right” if they further the mission, vision and values of the school that came from this work, as they are not random acts of improvement, but in fact are very strategic.