Guest Post – Chatterbox by Lou Tribus

I teach a Year 4 class in a small private primary school in central London. That would be the equivalent in the USA, by age of a 3rd grade class or academically of a 4th grade class. One of the benefits of a small private school is small class sizes: I had 12 children last year. Another benefit is that we have more freedom to be creative with our curriculum: we are guided, but not bound by the UK National Curriculum. This has allowed me to find small ways to introduce quality tools and systems thinking to my pupils.

I have taken small steps to teach quality methods to my class for the last seven years, since attending a David Langford course. My pupils have enjoyed learning to use fishbone diagrams, flow-charts, parking lots, hot-dots, pdsa planning sheets and capacity matrices. I have also introduced 5 whys, and if-then diagrams. I’ve used these tools to solve problems at school and to help them write better stories or solve maths problems. I haven’t however, collected much data, nor have I used data with the children as part of the quality process.

Determined to change this, I declared that 2012-2013 would be my Year of Data. One large board in my classroom had run charts for weekly whole class total spelling and mental maths scores, weekly whole class totals of how many rewards or sanctions given to the children, and one chart labelled “chatter”. (Rewards and sanctions are school policy, unfortunately.) The children also had individual run charts in their books for weekly maths and spelling scores. They charted their own progress weekly. I did not put individual scores on the board. My intention is to look at the system, not make children feel like failures if their scores are low.

I had a very lively class. They would burst into chatter at the least provocation. Like many children, they had not yet learned to moderate their own behaviour and depended on adults to do it. This is normal: children do learn to moderate their behaviour at different rates. It can be quite exhausting to have a group of immature children who depend entirely on you to keep their behaviour in control. Sometimes I felt I couldn’t relax for a moment. They agreed with me that “chatter” was our number one problem and they wanted to improve.

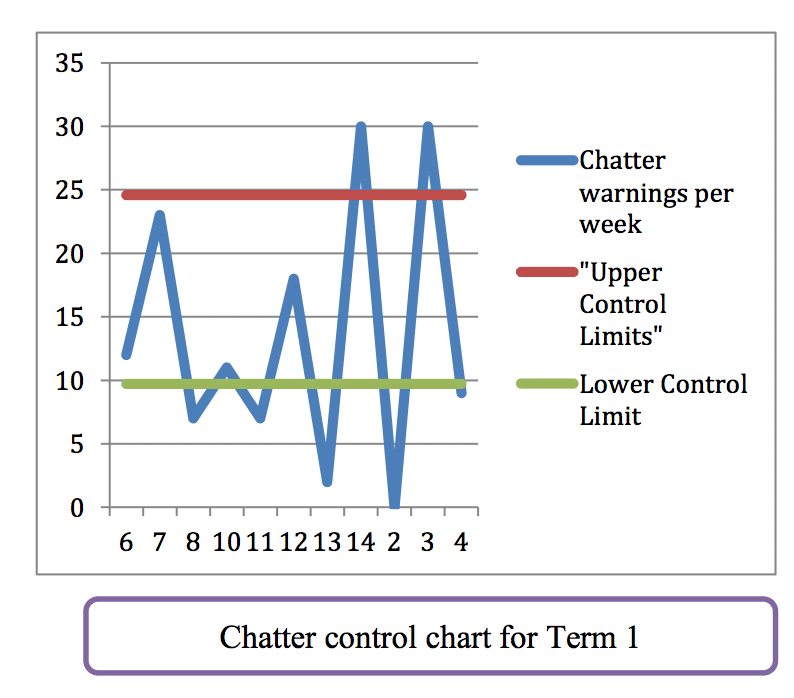

So we began to keep a control chart of how many times each day the children get told off for chattering (a “chatter warning”). By Christmas it was becoming a very interesting chart, with a sharply zig-zag line. In February, I calculated the upper and lower control limits based on a term and a half of data and presented the chart to the class. I really did not know what they would make of it.

So we began to keep a control chart of how many times each day the children get told off for chattering (a “chatter warning”). By Christmas it was becoming a very interesting chart, with a sharply zig-zag line. In February, I calculated the upper and lower control limits based on a term and a half of data and presented the chart to the class. I really did not know what they would make of it.

Immediately, most understood that something exceptional had happened at week 14 of the first term, and week 3 of the spring term that made them chatter more than usual. (Christmas week, and a trip to the National Army Museum). We didn’t know what happened in week 13. In week 11, I was ill and missed two days of school, and in week 2 of the spring term. I declared an amnesty on chattering as I was too busy to deal with it! I was amazed that they understood the chart so quickly, and even more amazed when one boy identified the area between the control limits as “normal”, declaring that “a little chatter from children is normal!”

The next step was to discuss and try out strategies to improve the situation. The children discussed the questions “When is it ok to chatter? When is it not allowed?” They came up with two lists for each situation.

Chatter is allowed: during free time, at play time, at lunch, on the bus, when changing for PE or swimming etc..

Chatter is not allowed during a lesson, when an adult is speaking, when lining up, when moving around the school and during transitions. I was interested to discover that the children could explain the reasons why they shouldn’t chatter in the first four instances, but they didn’t know what a transition is. It is the short interval between lessons, or within a lesson when we change from one activity to another.

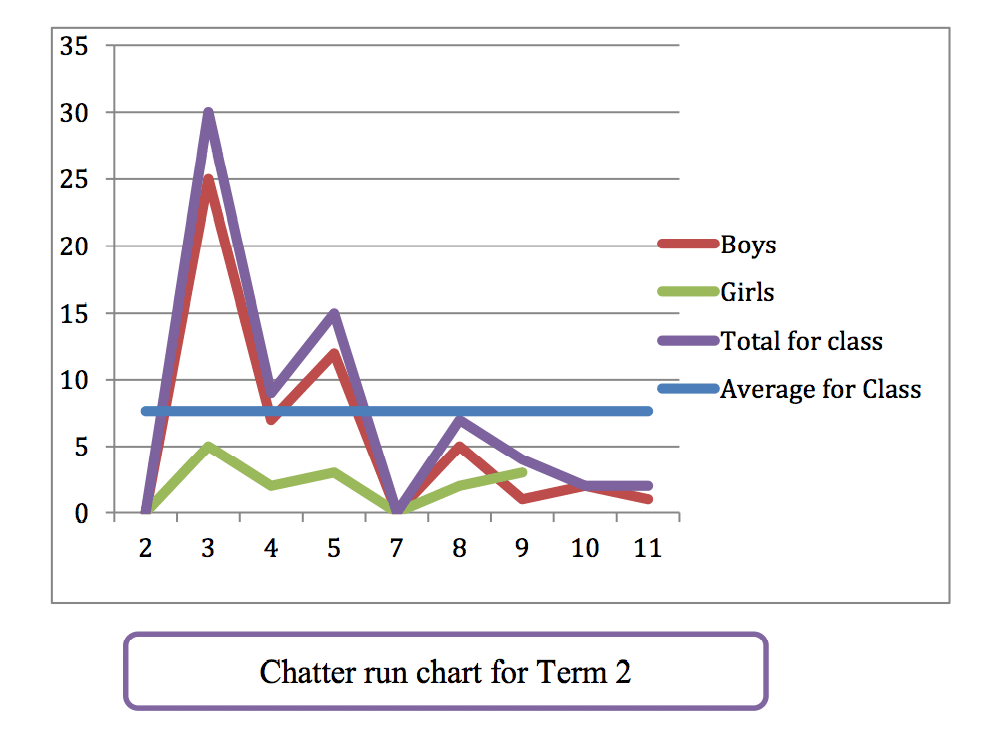

Here are some of their suggestions for improvement, and the run chart showing the effect of our changes. We tried out a new strategy every week.

- Mrs Lou should be very, very strict, shout every time anyone chatters and give out lots of chatter warnings.

- Make separate charts for boys’ chatter and girls’ chatter.

- We should change the configuration of the classroom so that children face forward instead of being in groups facing each other.

- Rewards for a good week with little chatter – 10 minutes free play at the end of the week.

- Mrs Lou should remind the children when we are in a transition.

In the beginning of the Spring term (wk3) we tried the “strict” approach. I shouted and nagged and scowled at every noise they made! When the children saw the data, they agreed that it didn’t work. Changing the configuration of the tables made a small difference as did taking separate data for boys and girls. (Chatter was clearly more of a behaviour issue for the boys than the girls!)

In my opinion, which I think is supported by the data, the most effective strategy was to determine, as a group, an operational definition of “chatter”, set parameters for when it is and is not allowed and why. We also came up with a definition of “transition” and discussed why transitions should be chatter-free. As a class we had a single purpose: to make the experience of being in Mrs Lou’s class more enjoyable for everyone by reducing the amount of chatter at certain times. By the end of the term, children were routinely reminding each other “No chatter, it’s a transition!”

I would be exaggerating if I said that there was no more chatter in my class. However I can say that it was no longer a big problem. As a class we could move on to other things, such as learning about life in Victorian London. The children in my class were very happy not to be living in an era where they would have been caned for chattering during a lesson!

Lou Tribus

London, UK, September 2013

Lou Tribus is the daughter of Myron Tribus. She was born in Los Angeles but spent most of her early life on the east coast of the USA. She received her Masters in Library Science from Indiana University in 1979. She lived in Haifa, Israel for 6 years and then moved to London, England. After teaching computer skills to small children for 14 years, she returned to university to earn a Post Graduate Certificate in Education (UK teaching qualification) at the University of Hertfordshire in 2006. She has worked as a primary school teacher for the last 8 years. In 2007 she attended a David Langford Quality Learning Seminar in Australia.

Lou has spoken about her work in the primary school classroom at the annual Facilitators’ Conference of the Universal Improvement Company in the UK since 2009.

Related: Deming’s Ideas Applied in High School Education (Sitka, Alaska) – Dr. Deming Video: A Theory of a System for Educators and Managers – Change has to Start from the Top – Webcast with David Langford