Post by Bill Bellows, Deputy Director, The Deming Institute

The first step is transformation of the individual. The individual, transformed, will perceive new meaning to his life, to events, to numbers, to interactions between people.

W. Edwards Deming

In January 1970, John Lennon returned to the UK from a holiday in Denmark, inspired by a series of stirring late night conversations, and began to compose a song about the timeless theory of the circle of life, “what comes around, goes around.” Ten days later, Instant Karma! was released and on its way to the top in the US and UK, competing for radio air time with Let it Be, offering Lennon’s sentiments on circular causality through a joyful chorus of “Well we all shine on.”

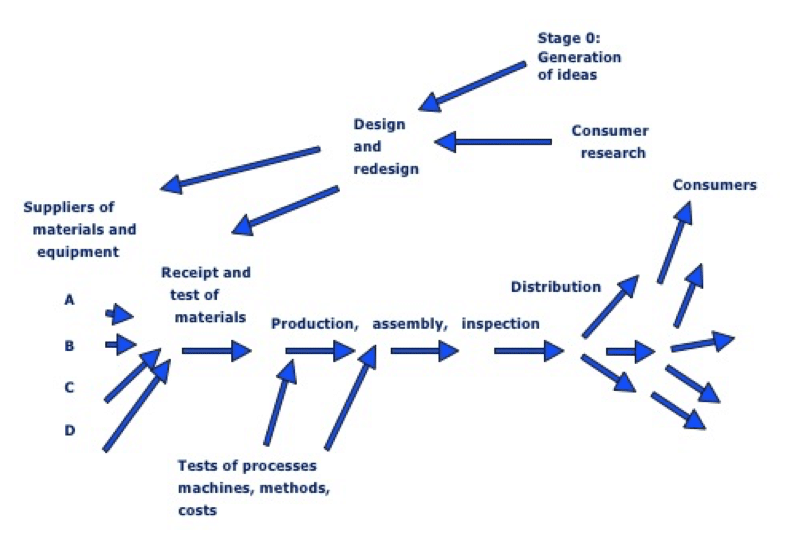

Twenty years earlier, in the summer of 1950, W. Edwards Deming was in Japan, invited by the Japanese Union of Scientists and Engineers to share his ideas on management with business leaders and wide cross sections of their organizations. In one event, he recalled hosting a group of executives representing as much as 80% of the corporate wealth of Japan. He used the opportunity to introduce his own karmic thoughts on the potential of “interactions between people,” with applicability to any organization, including government, education systems, and healthcare. His circular model, “Production Viewed as a System,” features a feedback loop to link the activities of a production-based organization, from design to manufacturing, with materials from suppliers, to assembly and release to the customer.

Production Viewed as a System

Chart first used by W. Edwards Deming in August 1950 in Japan

Source: The New Economics, Chapter 3, page 58

Change the context to a service industry, education system, or healthcare system, and replace the labels to their respective function to project this circular model onto any organization, with the premise that interdependent activities, otherwise known as teamwork, represent an invaluable, yet often invisible, phenomenon in all organizations. In a radical departure from the conventional linear view of the beginning of any value stream (such as product design), leading to an end point (release to the customer), Dr. Deming included a return loop to provide feedback to the entire design-to-release process, opening imaginative minds to the interdependency of these efforts.

In the spirit of applying the feedback loop in his own interactions with people, Dr. Deming employed this very model in his classroom at New York University, when he used the students’ answers to his questions, to let him know how well he was doing and, thereby, how to improve his lectures. He understood interdependence; their ability to learn depended on his ability to present. In his references to the prevailing style of management, Dr. Deming was mindful of the impact of the linear model in creating behaviors within organizations that could be also characterized as observer-status. Under such a system, players on the sideline of a football match would not appear to be influencing the outcome of the game, in spite of their contributions during practice sessions. In the nature of Instant Karma!, they would never be spectators, even if viewing from home, while recovering from an injury or retired from play. They would always shine on.

As he approached his 80th birthday, Dr. Deming was featured in a television documentary (If Japan Can, Why Can’t We?) in the summer of 1980, with a focus on the contrast between the gloom facing the U.S economy and the remarkable success of the Japanese economy. In reflecting on his advice to US companies for competing with their Japanese counterparts, near the 1:06 mark he proposed “I think that people here expect miracles. American management thinks that they can just copy from Japan, but they don’t know to copy.” Thereafter, he offered that his solutions should not be construed as quick fixes, “It will not happen at once, there is no instant pudding!” (In his book, Out of the Crisis, on page 126, he attributed the term “instant pudding” to James K. Bakken of the Ford Motor Company). As encouragement, he posed that results could be achieved within a few years, sharing examples from Japan. In time, Toyota would become one of the most celebrated examples, when Dr. Deming’s ideas on quality management were integrated into an existing system of quantity management.