Guest post by Mustafa Shraim, ASQ Fellow and Assistant Professor, Department of Engineering Technology and Management, Ohio University

“Variation is life or life is variation” is how Dr. Deming described the extent of what we observe in our personal and work outcomes. If the outcome can be measured, like the commute time to work or school, one can easily show fluctuation from one day to the next. The variation observed may be attributed to controllable factors, such as departure time, as well as those beyond one’s control, such as weather and traffic conditions. If the commute time averages 20 minutes, it may take 23 or so minutes when traffic is dense or 18 minutes when weather conditions are favorable.

So variation is expected – how we react to it is what’s important!

Shewhart determined that there are two types of mistakes that can be committed1. These come from the misclassification of the types of variation:

- Mistake 1: Reacting to an outcome as if it came from a special-cause variation when it really came from a common cause

- Mistake 2: Treating an outcome as if it came from common causes of variation when actually it came from a special cause

The first mistake is called tampering. Merriam-Webster dictionary defines tampering as “interfering so as to weaken or change for the worse.” Dr. Deming demonstrated the impact of tampering using his well-known funnel experiment. Examples of tampering abound: from continuously adjusting machine parameters in order to produce an acceptable product, to reaction of Wall Street to news or even reacting to rumors1. This phenomenon can be observed in production processes as well as management processes. It is the wrong reaction to the type of variation observed!

I recently published and presented a paper on tampering at the 2018 American Society for Engineering Education conference, where volunteers in an educational setting performed an experiment. In this experiment, we asked a team of students to run a catapult (process) without prior knowledge about any learning outcomes. The aim of the experiment was to introduce the concept of tampering to engineering students at the undergraduate level.

As is the case for any process, the catapult has controllable factors that can be set to increase or decrease the distance reached. There can also be some variability coming from noise such as slight movements while launching, inspector’s position when reading the distance, among others. To summarize, the experiment involved three scenarios:

(1) Run the process as is – no adjustments allowed.

(2) Hit the target distance (80 inches) – make adjustments as needed.

(3) Run the process as is – but after collaborating as a team and making simple improvements.

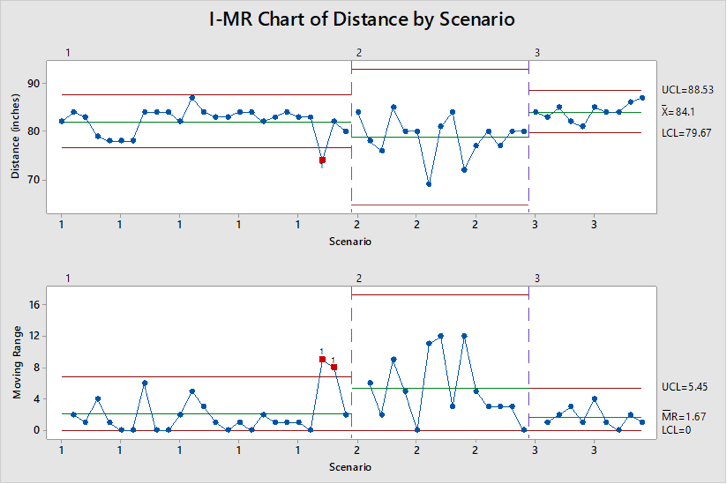

The results were not surprising, and confirmed the funnel experiment. The distance was plotted on an individual and moving range (I&MR) control chart, shown below, with three stages (scenarios).

*Note that the out-of-control point in Scenario (1) was identified as a slip of hand when launching the catapult; it was not removed, to show how such conditions can be detected by a control chart.

Scenario (2), where the volunteers made what they felt as the necessary adjustments to hit the target value, had the most variation. It should be mentioned here that Scenario (2) is like Rule 2 of Deming’s funnel experiment.

Scenario (3), on the other hand, represents a proper way of improving the process after working on the system – not reacting to each point. In this scenario, the team made sure that the catapult was not moving while launching and that the method of holding and launching was the same. This approach shows a significant decrease in variation.

The question that might be raised is: Why would we tamper if the process is stable (in control)? Here is a quote from Dr. Deming in The New Economics, 3rd Edition, page 139 on this very topic:

“A process may be stable, yet turn out faulty items and mistakes. To take action on the process in response to production of a faulty item or a mistake is to tamper with the process. The result of tampering is only to increase in the future the production of faulty items and mistakes, and to increase costs – exactly the opposite of what we wish to accomplish.”

Want more?

For the full-length paper on this tampering presentation, please click here or use this link: https://www.asee.org/public/conferences/106/papers/23451/view

Also check out: The Funnel Experiment with Brian Hwarng